How students exploit disability accommodations at universities

Bogus disability diagnoses lead to uneven academic standards.

Over the past 2 decades, university students have increasingly sought disability diagnoses in order to get extra time in their exams. Rose Horowitch wrote an extensive article called “Accommodation Nation” in The Atlantic to summarize this trend, and she offered some alarming statistics.

At the University of Chicago, the number of students who qualify for accommodations has more than tripled over the past 8 years. At the University of California at Berkeley, it has nearly quintupled over the past 15 years.

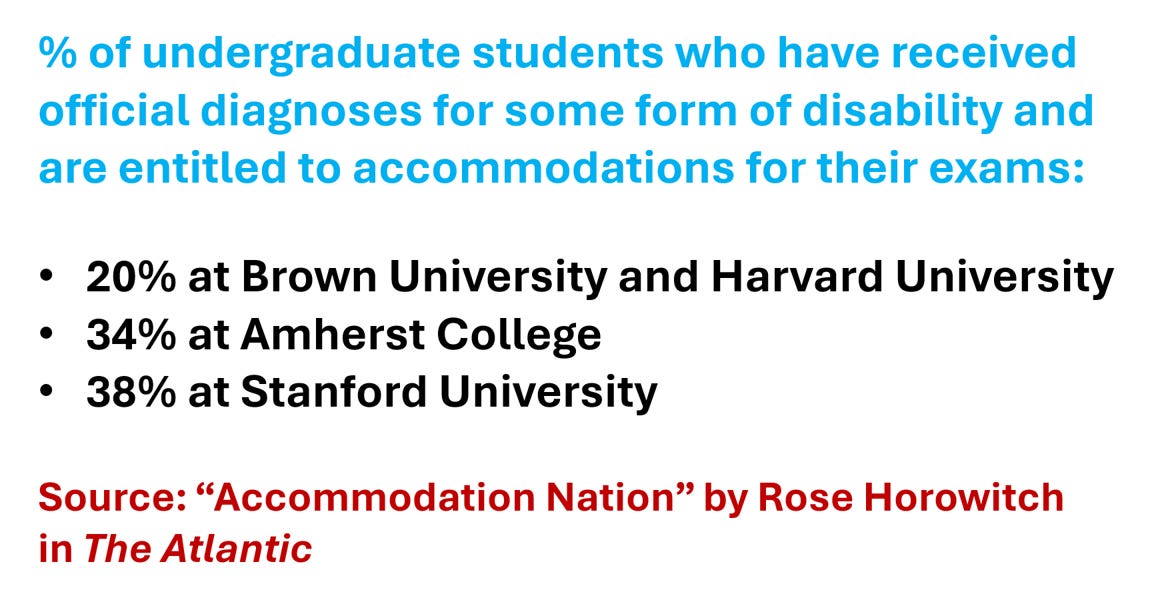

Here are the percentages of undergraduate students who received official diagnoses for some form of disability:

20% at Brown University and Harvard University

34% at Amherst College

38% at Stanford University

How did these diagnoses skyrocket? As Horowitch explained in her article,

The increase is driven by more young people getting diagnosed with conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, and depression, and by universities making the process of getting accommodations easier.

This violates the original intent of disability accommodations. If someone has a physical disability (like paraplegia) that is completely irrelevant to her mathematical reasoning, it makes sense for the university to provide ramps, elevators, and easy access to her classrooms.

Mental-health conditions and learning disabilities are completely different, because they directly affect a student’s ability to learn an academic subject. I am sympathetic to the plight of students who truly suffer from these conditions, but that does not justify loosening the testing standards. If you cannot find the eigenvalues of a matrix, then you have not learned linear algebra properly. A test should identify this failure - no matter what the cause is.

I found the following anecdotes to be particularly troubling:

One administrator told me that a student at a public college in California had permission to bring their mother to class. This became a problem, because the mom turned out to be an enthusiastic class participant.

Students at Carnegie Mellon University whose severe anxiety makes concentration difficult might get extra time on tests or permission to record class sessions, Catherine Samuel, the school’s director of disability resources, told me. Students with social-anxiety disorder can get a note so the professor doesn’t call on them without warning.

When you work in the private sector, your client or boss will impose deadlines on your assigned tasks, because time is valuable. If you cannot meet those deadlines, you will cause delays, lost productivity, and lower profits. These are real consequences that affect people’s livelihoods. Thus, when universities impose a time limit on your test, it is mirroring this reality.

An exam can only retain its value for comparing students if it is standardized in terms of difficulty, and the time limit is one aspect of that difficulty. When a university makes an exam easier for some students (but not others), then it is harder to compare these students fairly. For hiring managers in the private sector, this lack of standardization distorts the selection process.

I am a statistician and mathematician who cares a lot about the future of my profession, and I want hiring processes to become better at identifying qualified students to work in internships and permanent jobs. Bogus diagnoses and unjustified accommodations make this process harder.

Robert Weis is one of the psychologists who spoke to Rose Horowitch for this article. As Horowitch explained further,

Studies have found that a significant share of students exaggerate symptoms or don’t put in enough effort to get valid results on diagnostic tests. When Weis and his colleagues looked at how students receiving accommodations for learning disabilities at a selective liberal-arts school performed on reading, math, and IQ tests, most had above-average cognitive abilities and no evidence of impairment.

The only way to fix this problem is to overhaul this culture and restrict accommodations to students whose disabilities are completely irrelevant to their academic competence. The only people who can overhaul this culture are academic administrators, so I urge all departmental chairs, faculty deans, and university presidents to read “Accommodation Nation” seriously. You are the ones who have the power to make exams truly standardized and judge students on equal grounds. The labour market and the business world depend on you to make this process fair.

Strong data-driven argument about how accomodations distort standardized comparisons. The distiction between physical disabilities irrelevant to cognition versus mental conditions that directly affect learning is crucial but rarely made explicit in policy debates. I've seen hiring managers struggle with interpreting academic credentials when time limits vary wildly between students. The quintupling at Berkeley in 15 years suggests something beyond genuine need expanding.